Hard path versus soft path solutions

Hard path versus soft path solutionsI was out hiking in the Whiteshell Provincial Park last week, enjoying the beauty of pine forests, ankle-deep moss underfoot and broad warm shoulders of granite everywhere. The Whiteshell is located on the western edge of the Canadian Shield, which Wikipedia tells us is “the first part of North America to be permanently elevated above sea level … almost wholly untouched by successive encroachments of the sea upon the continent. It is the earth's greatest area of exposed Archaean rock,” about 2.5 billion years old.

Most of the granite, heated by hundreds of thousands of summers, is pretty flat. There are plenty of places, in fact, where areas of granite are used as makeshift parking lots for campers to leave their vehicles while they go fishing or hiking.

But not all of it. Quite a lot of places, you will find vertical drops or fissures in the rock, so it is not altogether wise to walk along dreamily looking up at the hushed cathedral of pines above you. Too much of that, and the cathedral could suddenly echo with unbecoming shrieks.

Unbecoming shrieks are definitely coming up over the next few decades, unless we look at where we're going and take care to find a soft path down.

What the heck is a soft path? It is an idea -- an idea that could save us a lot of pain and trouble as we make our way into a very different future.

It consists of knowing where you are, knowing where you are going to be or where you want to be in the future, and then charting a path between those two places, a path that does as little damage and costs as little as possible.

Although parts of a properly planned soft path may look expensive, or even look absurd, at the endpoint a disastrous, chaotic transition will have been avoided, preserving rather than risking the fragile resources which might otherwise be lost. Metaphorically, jumping down the crevice is likely to lose you your radio, your flashlight or your flask of brandy. Climbing down, though slower, will ensure when you're camped that night you'll still be able to have a quiet drink while listening to As It Happens and studying your map.

Right-wing thinkers often say that change is inevitable, and that destructive change can even be a good thing -- "creative destruction", leading to a new, cleaner, more efficient social or business structure. While this is sometimes true, a study of economic history over the past two or three hundred years might lead a careful reader to wonder how much of that destruction was actually necessary, and how much of it fell upon the shoulders of those ill-suited to fight back. A truly cynical reader might ask herself if the concept of creative destruction was most useful for persuading people that their personal destruction was both necessary and good.

In the 90s Canadian philosopher John Ralston Saul gave the Massey Lectures, with his topic titled "The Unconscious Civilization". The lectures, and the book which included them, were well worth reading (and still are), but like some other influential books, the title itself is sufficient to pull a lot of the weight of his arguments.

Exactly how much of the decision-making of nations is actually conscious? We see glimpses of it here and there, and one of the things I love about Canada is that I believe our government acts consciously somewhat more often than others. I offer as proof our health care system, the CBC, and in a twisted way that most peculiar element of our Charter of Rights and Freedoms -- the Notwithstanding Clause.

But how helpful is it, really, to be conscious for a few minutes a day, while spending the rest of the time running on pure reflexes? If you are not a morning person, I will cut you a lot of slack before you've had your coffee. But morning person or not, staggering around driven by emotions, primate social competition, or your own misconceptions is going to drop you right into the Canadian Shield.

Back to the soft path. How do you apply this simple concept to the big, apparently intractable problems facing Canada right now? Let me take one -- the crisis facing rural and farming communities.

Many of these communities are tottering on the edge of a tipping point into ghost town status. Taken to its logical conclusion, if Canadians who live in rural communities don't have enough income or the resources that they need to get to the store, to church and to their friends homes, if they don't have a large enough population density to support schools to educate their children, hospitals to serve their health needs and care homes where the elderly can retire in their own communities -- then they won't.

My nightmare vision of a Canada without a rural presence is one where if you want to drive cross-country you would pack supplies, a GPS emergency beacon and extra fuel. It's a vision that sees enormous expanses of Canada the de facto domains of unregulated factory farms. It's a vision that makes me ask -- if Canada consists of a couple of dozen large cities with nothing but greenery or corporate enclaves in between, exactly how secure are we?

Luckily for the rest of Canada, rural people are amazingly stubborn and resourceful. But there are limits even to rural stubbornness.

The hard path we might tread by not consciously facing the problem of rural depopulation includes possible outcomes than I, for one, find unacceptable. We are a long ways along this path -- Canadian population shifted from 80% rural to 80% urban over the past 70 years or so. (Although I believe most of this change has to do with the rural population staying the same while most of the population growth happened in cities.)

A soft path approach to this depopulation problem would begin by establishing (for the sake of planning) what level of population seems to be desirable, and looking at what services and supports would be necessary to keep such communities prosperous.

There is no time in this post, which has already gone on way too long, to lay out even a rough draft of such a plan. Such a draft all by itself would probably take a couple of years, even with the assistance of a multitude of studies which have already been done, and a wiki of planners.

However, remember a few paragraphs up where I talked about absurd or even apparently expensive parts of a soft path plan turning out to be actually necessary? A sample of one of these counterintuitive initiatives might be biodiesel and ethanol production.

In terms of energy production, both of these are silly. Growing crops in order to turn them into cooking oil in order to put that in a car's engine and burn it as fuel is as goofy as raising, slaughtering and drying out chickens to use as firewood. Ethanol production is much the same. I don't have the statistics right at hand, but the energy balance -- the amount of energy you have to put in in order to get an equal amount out again -- is much too close to level to make any sense in addressing climate change.

But in the short term, both of these provide a way of ensuring a steady income for a multitude of farmers, even if the crop suffers a poor year and lousy quality. Yeast doesn't care if grain doesn't make good pasta, it doesn't even care (I think) if there is all manner of grain smut, mold, mouse droppings or ground-up blister beetles in it. I could be wrong about this, but I would think that so long as you can scrape it up off the field, you can ferment it.

As part of a soft path plan to support rural communities until a new balance can be established, biodiesel and ethanol production deserve a blue ribbon.

Not too many people talk about soft path planning. But they should. Otherwise, in years to come all the shrieking is likely to keep us awake, and we won't even have brandy to get us back to sleep.

=====================

Correction 6:30 a.m. "Charter of Rights and Freedoms", not "Constitution". --NM

Hurricane Gustav has thrown America's political agenda into chaos with the biggest casualty being the Republican convention, which was due to open tomorrow in Minneapolis-St Paul, Minnesota.

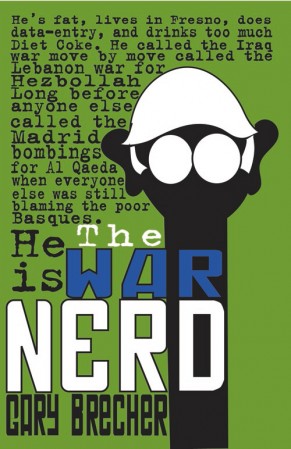

who has wit and perception. Gary can be found on a site called

who has wit and perception. Gary can be found on a site called